From AFFF to F3 : Regulation and Legislative Pressures — Part 5

Previous articles (Parts 1 to 4) have dealt with the history, chemistry, environmental and health impacts of PFAS exposure.

Introduction

Regulators have become increasingly aware of the risks implied by the manufacture and use of perfluorinated compounds in industrial and consumer products and, as a result, many countries have enacted legislation restricting the use and disposal of PFAS.

Lack of knowledge of best available practice (BAP) or the law is no defence when it comes to defending one’s actions that may have led to environmental contamination, as encapsulated in the legal phrase “ignorantia legis neminem excusat (“ignorance of law excuses no one”)”. This doctrine first shows up in the Bible in Leviticus 5:17: “If a person sins and does what is forbidden in any of the Lord’s commands, even though he does not know it, he is guilty and will be held responsible.”

A modern interpretation of this principle has been established under the Rio Convention in 1992 as the precautionary principle under which lack of evidence must not be treated as evidence of lack of harm, especially where long term intergenerational effects may be suspected.

The REEBOK seminars

Shortly after the announcement by the 3M Company in May 2000 that they were withdrawing from PFOS-based chemistry, RAK and his colleagues arranged a series of international conferences in Manchester and Bolton to discuss environmental issues associated with firefighting foams. These Reebok seminars which took place in 2002, 2004, 2007, 2009 and 2013, were well attended by the fluorochemical industry, regulators, foam manufacturers and end-users such as fire departments worldwide. These seminars became the de facto industry forum for discussing the phase out of Class B AFFF and the transition to Class B fluorine-free foams (F3).

At the earliest Reebok seminar in 2002 it was pointed out that the U.K. GroundWater Regulations 1998 already prohibited the discharge of fluorochemicals as found in AFFF foams to groundwater if they were PBT – Persistent, Bio-accumulative and Toxic. Unfortunately given clear lack of knowledge of the significance of the term ‘organohalogen’ of the regulation (SI 2746/1998) it was claimed that this was not relevant.

Later Reebok seminars, especially in 2004 and 2007, concentrated not just on PFOS but also on PFOA and related substances that could degrade to PFOA, a typical perfluorinated extremely persistent PFCA end-product of breakdown. The possibility of derivatives such as 8:2FTS, as found in C6/C8 fluorotelomer foams, bio-degrading to yield PFOA was at first vigorously denied by the fluorochemical industry in the face of published evidence suggesting the contrary. However, the whole tenor of the discussion changed as a result of pressure from the US-EPA which resulted in the 2010-2015 PFOA Stewardship Programme leading ultimately to a requirement for fluorotelomer products to contain less than 25 ppb PFOA or its precursors.

i) 1998: Subject to sub-paragraph (2) below, a substance is in list I if it belongs to one of the following families or groups of substances–

(a) organo-halogen compounds and substances which may form such compounds in the aquatic environment;

ii) 2009: This includes in particular the following when they are toxic, persistent and liable to bio-accumulate—

(a) organohalogen compounds and substances which may form such compounds in the aquatic environment;

UBA

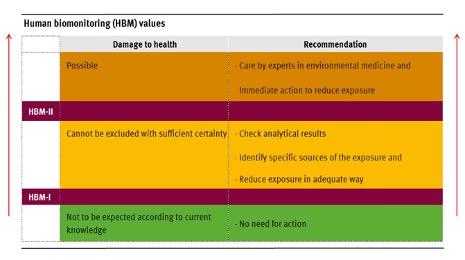

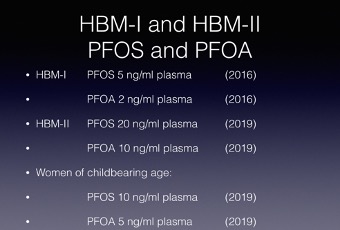

The German Federal Environment Agency’s (das Umweltbundesamt or UBA) Human Biomonitoring Commission has established trigger levels for both PFOS and PFOA in human blood plasma. The HBM-I value is the plasma concentration in ng/ml (ppb) that is estimated to pose no appreciable risk to the human population for prolonged exposure and, thus,no need for further action. Concentrations between HBM-I and HBM-II indicate that health impacts cannot be excluded with sufficient certainty and that further investigation is necessary with the introduction of measures to eliminate, reduce or control exposure, including identifying potential sources and checking analytical results. Plasma concentrations in excess of HBM-II values, indicating possible health impacts, require immediate intervention to reduce or eliminate exposure and assessment of any health impacts.

The HBM-I and HBM-II values for PFOS and PFOA are shown below. For women of child-bearing age the HBM-II values recommended are half those for the general population. It is worth noting the PFOA values are less than those for PFOS.

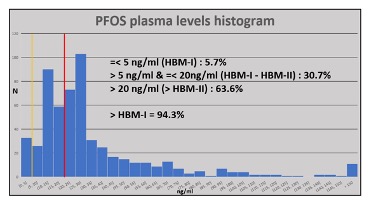

FIREFIGHTERS EXPOSURE

The story for firefighters who are or have been occupationally exposed to PFAS-based AFFF is a rather different story. Long service firefighters as well as those more recently employed may have plasma levels far in excess of acceptable values especially for PFOS and its homologue PFHxS, which are correlated. As an example, the figure below shows PFOS plasma levels in 2015-2016 for an extensive cohort of firefighters from a large Australian fire brigade, in which the majority had levels in excess of HBM-II. THE HBM-I level is shown as the yellow vertical line, HBM-II in red. Nearly 2/3 of the sampled cohort exceeded HBM-II indicating a potential health risk.

The major exposure pathway for firefighter exposure to PFAS is clearly the use of AFFF fluorochemical containing firefighting foam either operationally or during training and maintenance. The mechanism of exposure is undoubtedly either the inhalation of foam aerosol especially for those personnel not wearing self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), or through dermal absorption as a result of being soaked with foam spray. At any major incident involving foam, for example a fuel tank fire, approximately a third of the foam applied from monitors never reaches the fire itself but is lost as a foam curtain and aerosol which contaminates the surrounding area and any personnel present.

Drinking water

Drinking water is the one unavoidable exposure pathway for everyone. Average intake is calculated as ~2 litres/day over one’s lifetime. Maximum total weekly intakes (TWI) are calculated on this basis.

The revised EU Drinking Water Directive entered force in January 2021, with full compliance by 12 January 2023, and included measures tackling emerging contaminants such as endocrine disruptors and PFAS, as well as microplastics. The maximum concentration of all PFAS compounds combined 0.5 μg per liter of water (500 ppb). Alternatively, member states can monitor the sum of 20 specified PFAS compounds, for which the maximum is 0.1 μg/l (100 ppb).

The Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RVIM) has recently derived new limits risk limits for PFAS in surface waters [*2022-0074 RVIM 2022-09-08] based on EFSA derived health-based values for PFAS in 2020. The new risk limits are 0.3 ng/l (0.3 ppt) for PFOA, 7 pg/l (0.007 ppt) for PFOS), and 10 ng/l (10 ppt) for Gen-X. These are much lower than current standards for these PFAS.

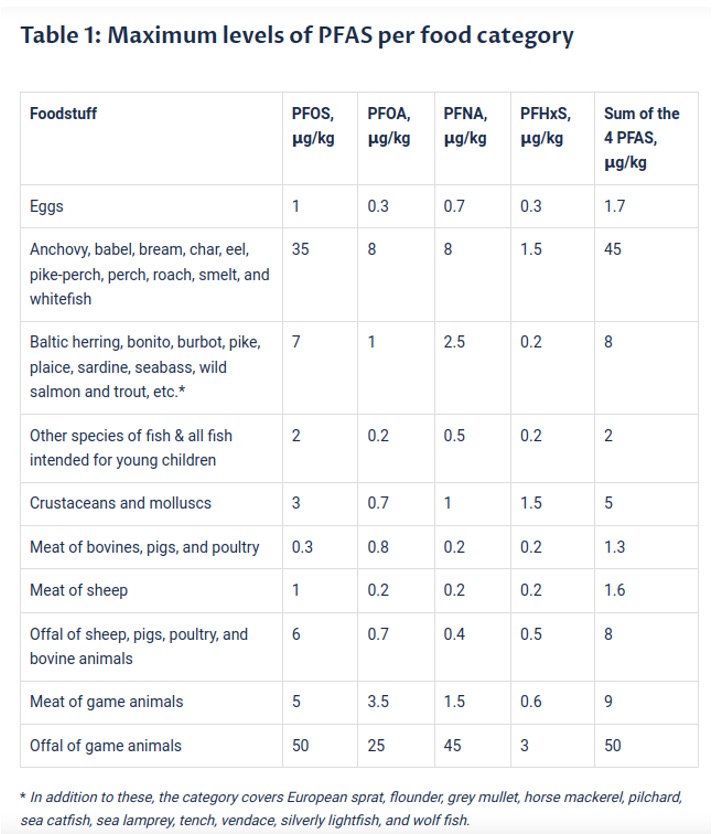

Food

The limits on PFAS in selected food products on the EU market are listed in Table 1. If higher concentrations are discovered in laboratory tests, the product has to be removed from the market.

UN – Stockholm Convention for POP

The Intergovernmental Forum on Chemical Safety (IFCS) and the International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) prepared an assessment of the 12 worst offenders, known as the dirty dozen, as the initial POPs listed under the Annexes of the Stockholm Convention. These substances included the pesticides Aldrin, Chlordane, DDT, Dieldrin, Endrin, Heptachlor, Hexachlorobenzene HCB, Mirex, Toxaphene; and the industrial chemicals polychlorinated biphenyls PCB, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins PCDD and polychlorinated dibenzofurans PCDF.

The INC met five times between June 1998 and December 2000 to elaborate the convention, and delegates adopted the Stockholm Convention on POPs at the Conference of the Plenipotentiaries convened in May 2001 in Stockholm, Sweden. The convention entered into force on 17 May 2004 with ratification by an initial 128 parties and 151 signatories. Co-signatories agreed to outlaw nine of the dirty dozen chemicals.

The first set of new chemicals to be added to the convention were agreed at a conference in Geneva on 8 May 2009.

In 2009, perfluorooctane sulfonic acid and its derivatives -PFOS- have been included in the UN Stockholm Convention to eliminate their use (decision SC-4/17). In 2019, following the evaluation by POPRC-14 in 2018 at FAO Headquarters in Rome of the continued need for PFOS, its salts and PFOSF, COP9 amended Annex B to remove several of the specific exemptions and acceptable purposes for PFOS, its salts and PFOSF (decision SC-9/4).

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.2/17/Add.5: Risk profile for perfluorooctane sulfonate

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.3/20/Add.5: Risk management evaluation for perfluorooctane sulfonate

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.4/15/Add.6: Addendum to the risk management evaluation for perfluorooctane sulfonate

In 2019, COP9 listed PFOA and its derivates in Annex A to the Stockholm Convention (decision SC-9/12). POPRC Secretariat developed an indicative list of substances, originally containing around 4,700 compounds; the list is to be updated periodically. PFOA has been banned under the POPs Regulation since 4 July 2020.

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/11/Add.2: Risk profile for PFOA, its salts and PFOA-related compounds

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.12/INF/5: Additional information relating to the risk profile for PFOA, its salts and PFOA-related compounds

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.13/7/Add.2: Risk management evaluation on PFOA, its salts and PFOA-related compounds

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.14/6/Add.2: Addendum to the risk management evaluation on PFOA, its salts and PFOA-related compounds

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.17/INF/14/Rev.1: Updated indicative list of substances covered by the listing of PFOA, its salts and PFOA-related compounds

In June 2022, the UN Stockholm Convention also decided to include PFHxS and related compounds in the treaty. The Commission added the substance group in the EU’s POPs Regulation in May 2023 and the regulation entered into force on 28 August 2023.

The POPRC is currently reviewing LongChain-PFCAs, and related compounds, proposed for listing in Annexes to the Stockholm Convention.

• UNEP/POPS/POPRC.17/7: Proposal to list long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids, their salts and related compounds in Annexes A, B and/or C to the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

White Papers from IPEN PFAS Expert Panel 2018-2019

Three influential White Papers produced by the IPEN PFAS Expert Panel in 2018-2019, coordinated by Roger Klein and colleagues, were presented to the UN Stockholm Convention’s POPRC14 in 2018, COP9 and POPRC15 in 2019 discussing progress in transitioning from AFFF to F3 firefighting foams, issues associated with PFAS and PFHxS. These White Papers assisted the Committee in achieving the listing of these PFAS under the appropriate Annexes for restriction or banning in 2019 and 2022.

As of September 2022, there are 186 parties to the UN Stockholm Convention (185 states and the European Union). Notable non-ratifying states include the United States, Israel, and Malaysia.

EU Regulation

The first product to be regulated has been PFOS.

Norway prohibited the use of PFOS-containing materials in 2007.

The European Union Commission Regulation (No. 757/2010) required that all foam containing PFOS above 10 mg/kg (0.001% w/w or 10 ppm) must not be used after 27 June 2011 and this was adopted by the UK Environment Agency in February 2011.

In January 2014, the Environmental Agency of Norway has published the Regulation FOR-2013-05-27-550, which bans the use of PerfluroOctanoic Acid -PFOA- and its salts and esters.

Limits were implemented on July 1, 2014 to all products manufactured, imported, exported and marketed in Norway, with the exception of some specific articles for which the new rules were applied in January 1, 2016.

In 2020, EU 2020/784 regulates the use of PFOA and limits the content to 25ppb. In theory, it can be used until 2025 if all effluents can be contained, which is impossible to guarantee. In the facts, the regulation eliminates PFOA in Europe.

Long Chain Perfluorinated carboxylic acids (C9-14 PFCAs), their salts and precursors are restricted in the EU/EEA – EU Regulation 2021/1297 -from February 2023 onwards.

Germany – supported by Sweden, Netherlands, Denmark and Norway – has proposed a further restriction for PerFluoroHexanoic Acid C6 -PFHxA-, its salts and related substances. This proposal is highly significant as it would effectively ban the use of C6-fluorotelomer AFFF foams. This proposal was evaluated by ECHA in December 2021.

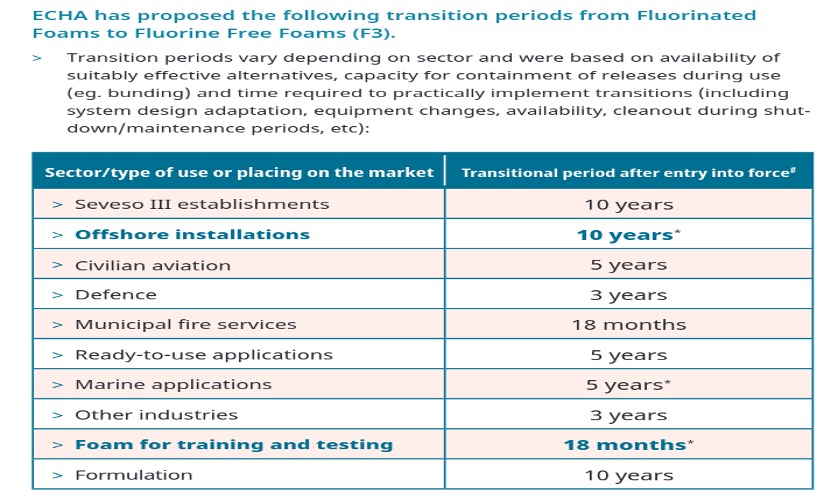

The European Chemical Agency -ECHA- is evaluating a global restriction on an EU-wide PFAS ban on firefighting foams. The restriction could reduce PFAS emissions into the environment by around 13 200 tons over 30 years [*June 2023 ECHA/NR/23/19]. An answer is expected to be given in January 2024.

Australia

Until recently, there has not been a Federal approach to regulate the use of AFFF in Australia; but each sate had its own way to restrict the use of fluorinated foams.

Canberra – Federal – published in May 2020 NEMP 2.0 to establish a practical basis for nationally consistent environmental guidance and standards for managing PFAS contamination. A draft of PFAS in NEMP 3.0 was released in September 2022.

Queensland

Queensland Fire Service is using F3 foam since 2003

Queensland Environment Authorities controls PFAS content of AFFF products and banned PFOS.

New South Wales

Fire Services had been using 3M’s foams; and stopped their use in 2007. The Protection of the Environment Operations Regulation 2022 bans and restricts the use of PFAS firefighting foam in NSW to reduce its impact on the environment, while still allowing its use for preventing or fighting catastrophic fires by relevant authorities and exempt entities. The Regulation aligns with the National PFAS Position Statement and is the first step to achieving the agreed objectives in the Statement.

Victoria

In 2007, Victoria Fire Service – MFB- made a decision to replace existing firefighting foam with fluorine-free firefighting foam. This decision was made on the basis of concerns relating to firefighter health and environmental issues. MFB developed an ‘Operational Use of Firefighting Foam Policy’ which was formally endorsed by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA), WorkSafe and the Country Fire Authority (CFA). During 2011, based on independent scientific studies into PFAS, that identified links to various cancers and other health concerns, MFB extensively trialled and Fire Rescue Victoria evaluated various fluorine-free firefighting foam in hot fire, flammable liquid, B Class fire scenarios. MFB found that the fluorine-free foam consistently performed well in extinguishing B Class fires and provided MFB firefighters with a proven ‘safer’ alternative extinguishing medium. This work provided MFB with an operational firefighting foam solution that could be effectively used at Department of Defence sites, such as RAAF Airbases at Point Cook and Laverton. This enables MFB and FRV to meet its obligations for the delivery of emergency services to Defence bases using firefighting foam that does not contain PFAS. By 2014, all MFB firefighting appliances had been converted to only carry fluorine free B Class foam in their foam tanks.

South Australia

A ban on fluorinated foams came into effect in South Australia in January 2018, but licensees have the opportunity to apply for an exemption in certain circumstances.

Western Australia

Outlined work has been undertaken to identify and manage PFAS in December 2017; but now following Federal NEMP.

Tasmania

TasPorts is a leader in Tasmania’s approach to managing PFAS and fully eliminated all PFAS-containing foams from the island.

AirServices

Since 2010, Airservices has carried PFAS-free fire fighting foam at all civilian airports where it operates.

New Zealand

New Zealand excluded PFOS and PFOA from use in any solid or liquid substances that are imported or manufactured for use as a firefighting chemical in the Fire Fighting Chemicals Group Standard 2006 under the NZ Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996.

Firefighting foam soil and water contamination has been reviewed in December 2020. Total ban of PFAS in firefighting foams will apply from December 2025.

Food Standards Australia & New Zealand (FSANZ) launched a monitoring of Perfluorinated Chemicals in Food since April 2017, with Health guidance for Daily Intake Dosis values for PFOS, PFOA and PFHxS.

Canada

Canada has always been at the forefront of awareness and regulation as regards the inherent and potential risks of releasing PFAS to the environment and exposing the human population to PFAS contamination through drinking water, agricultural products and domestic use.

The Government of Canada is considering activities that would address PFAS as a class rather than as individual substances or in smaller groups. Addressing PFAS as a class of chemicals would reduce the chance of regrettable substitution, support more holistic research and monitoring programs, and provide an opportunity for a decrease of future environmental and human exposure to PFAS. A notice of intent to address the broad class of PFAS was published in the Canada Gazette, Part I: Vol. 155 No. 17 – April 24, 2021.

In response to the commitment described in the notice of intent the Government of Canada has published a Draft State of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) Report for a 60-day public comment. The related notice was published in the Canada Gazette, Part I: Vol. 157, No. 20 – May 20, 2023.

Currently, only a limited number of PFAS subgroups are subject to regulation in Canada. PFOS, PFOA, LC-PFCAs and related derivates have been assessed and added to the List of Toxic Substances under Schedule 1 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA).

Since 2016, the manufacture, use, sale, offer for sale or import of PFOS, PFOA, LC-PFCAs, and products that contain them have been prohibited, with a limited number of exemptions under the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012. In May 2022, the federal government published a proposed new Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2022, which would replace the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012 and eliminate most exemptions allowing the use, sale, or import of PFOS, PFOA and LC-PFCAs in Canada.

Canada prohibited the use of foam containing PFOS above 0.5 ppm in May 2013, the regulation came into force in May 2008.

United States of America

In 2004, it was estimated that there was approximately 45 million liters of AFFF concentrate in the United States and its territories.

The National Defense Authorization Act passed by Congress in late 2019, required the US Navy to publish a new military specification for a fluorine-free foam by the end of January 2023 and required a full transition to fluorine-free firefighting foams by October 2024. Congress had imposed earlier mandates on the FAA to transition airports to fluorine-free foams by October 2021, but that deadline was missed. The new MIL-SPEC regulations pave the way for both FAA airports and military bases to transition, requiring significant investment. According to a 2021 Congressional report, the Military and Civilian airports still have about ~50 million litres of AFFF concentrate at its facilities. Although the military has yet to officially approve a f1uorine-free foam for use at its facilities, there now exist a number of commercially available products that have passed appropriate performance tests such as UL.

In the USA, every state has been going its separate way. The scandal of withheld fluorochemical toxicity and environmental impact information as well as outright misinformation, emerged from a long series of judicial court cases against PFAS feedstock manufacturers. The story even culminated in the publication of advertisements from attorneys looking for customers to go to court!

State governments are taking legislative and regulatory actions to phase out PFAS in products to prevent contamination in favour of safer alternatives. For example, laws in ME and WA have given state agencies authority to ban PFAS in a wide range of products. Maine’s law requires product manufacturers to disclose the presence of PFAS. Several states have adopted restrictions on PFAS in textiles with CA banning PFAS in almost all textiles by 2025, and NY restricting them in apparel, CO banning them in upholstered furniture, and WA moving forward on regulatory actions on many categories of textile products. Six states (CA, CO, ME, MD, NY, and VT) have adopted restrictions on PFAS in carpets, rugs and after-market textile treatments. Twelve states (CA, CO, CT, HI, MD, ME, MN, NY, OR, RI, VT, and WA) have enacted state bans on PFAS in food packaging. Four states (CA, CO, MD, and WA) have adopted restrictions on PFAS in personal care products. CO also adopted restrictions on oil and gas products. Eleven states including CA, CO, CT, HI, IL, ME, MD, NH, NY, VT, and WA have put in place bans on the sale of firefighting foam containing PFAS. With legislation adopted last year, WA is evaluating safer alternatives for PFAS in other products such as apparel, cleaners, coatings and floor finishes, firefighter turnout gear and others with a timeline of adopting restrictions by 2025. Source www.saferstates.org

Due to the judicial court cases, most of the national manufacturers ceased the production of AFFF foam in 2024 and started to promote fluorine-free foams, not only in the USA, but to all their traditional markets and customers.

Disposal of PFAS waste

This is huge and potentially extremely expensive problem. At major incidents such as Milford Haven (August 1983), Sandoz Basel (November 1986), Coode Island (Melbourne August 1991), , Buncefield (December 2005) or Campbellfield (Melbourne April 2019), tens of millions of liters of foam-contaminated firewater run-off were released to the environment – total containment at such large incidents is almost impossible and any waste that is collected must be disposed of appropriately. Legacy stocks of fluorinated foam concentrates represent a large financial expenditure as part of transitioning to fluorine-free products, as does the decontamination of fixed and mobile equipment.

Currently the most effective, financially feasible and environmentally sustainable method for disposing of large quantities of PFAS contaminated solid or liquid waste appears to be very high temperature incineration. Costs can range between 1000-3000 USD, strongly depending on the accepted level of residual fluorinated contaminant.

Summary

Evermore regulations, especially in Europe and Australia/New Zealand, are targeting especially dispersive applications using PFAS such as firefighting foams. The transition from AFFF to fluorine-free foams -F3- has become possible, given rapid technological advances in the last 5-10 years and fluorine-free products able to compete with AFFF based on performance.

Many large organizations such as civilian and military airfields, as well as Oil& Gas, Chemical, Mechanical industry such as Equinor, Bayer, Lufthansa and BMW, have already gone fluorine-free, having solved the problems of old AFFF equipment and appliance decontamination as well as compatibility in terms of delivery systems and operational training.

Most recently, we have seen some awareness growing in Environment Regulation Bodies – Singapore, Mexico, Colombia – showing a deep interest in what has been happening in other countries; it is likely that the ban on ‘’Forever chemicals’’ will be extended to the world community in the next 5 to 10 years !

References

Krogerus, M. (2012) The Decision Book: Fifty Models for Strategic Thinking. Tschäppeler, R. and Piening, J. (1st American edition), New York, W.W. Norton & Co., pp. 86-87.

Rumsfeld, D. (2002)

Rio Convention (1992)

United States (1933) Securities Act.

Preston, B.J. (2017) The Judicial Development of the Precautionary Principle. Queensland Government Environmental Management of Firefighting Foam Policy Implementation Seminar 21 February 2017, Brisbane, Qld., pp. 26.

Preston, B.J. (2018) ‘The Judicial Development of the Precautionary Principle’ Environmental and Planning Law Journal 135, 23-42.

Allcorn, M., T. Bluteau, J. Corfield, G. Day, M. Cornelsen, N.J.C. Holmes, R.A. Klein, J.G. McDowall, K.T. Olsen, N. Ramsden, I. Ross, T.H. Schaefer, R. Weber, K. Whitehead. (2018) “Fluorine-Free Firefighting Foams (3F) Viable Alternatives to Fluorinated Aqueous Film-Forming Foams (AFFF).” UN Stockholm Convention POPRC14 Rome 17-21 September 2018, IPEN Gothenburg Sweden: IPEN F3 Expert Panel. < www.ipen.org >

Bluteau, T., M. Cornelsen, G. Day, N.J.C. Holmes, R.A. Klein, J.G. McDowall, K.T. Olsen, M. Tisbury, and L. Ystanes. (2019) “The global pfas problem: fluorine-free alternatives as solutions firefighting foams and other sources-going fluorine-free.” UN Stockhom Convention COP9 Geneva Apr-May 2019, IPEN Gothenburg Sweden: IPEN F3 Expert Panel. < www.ipen.org >

Bluteau, T., M. Cornelsen, N.J.C. Holmes, R.A. Klein, M. Tisbury, and K. Whitehead. (2019) “Perfluorohexane sulfonate (pfhxs)-socio-economic impact, exposure, and the precautionary principle.” UN Stockholm Convention POPRC15 Rome Sep-Oct 2019, IPEN Gothenburg Sweden: IPEN F3 Expert Panel.

< www.ipen.org >